Developing a vaccine for Covid-19: what can we learn from past outbreaks?

Vaccines are one of our most powerful health tools. Not just for ending the current Covid-19 outbreak, but also for preventing the return of other deadly diseases. Here’s some of the lessons we’ve learned about the development and use of vaccines from past outbreaks.

Some countries are starting to see success in responding to Covid-19 through rigorous tracking, testing and isolation approaches. But for many vulnerable communities, only a vaccine will provide the final ‘exit strategy’.

This World Immunisation Week, we must celebrate the incredible work being done by the global research community in partnership with governments, academia and industry to develop a vaccine for Covid-19. In record-breaking time, we’ve seen an almost unbelievable feat of innovation in response to the outbreak, with the rapid sequencing of the virus published on 11 January 2020, the first human trials on 16 March 2020, and now 115 vaccines in development.

As well as celebrating these fantastic achievements, this week is also a chance to reflect on the lessons learned from past outbreaks, and what it really means to make vaccines work for all.

Research needs to be at the heart of the global response

To get ahead of outbreaks, we need a global research effort to develop vaccines and treatments. Putting research at the heart of the response is a double win – helping to fight outbreaks that are underway and protect us in future.

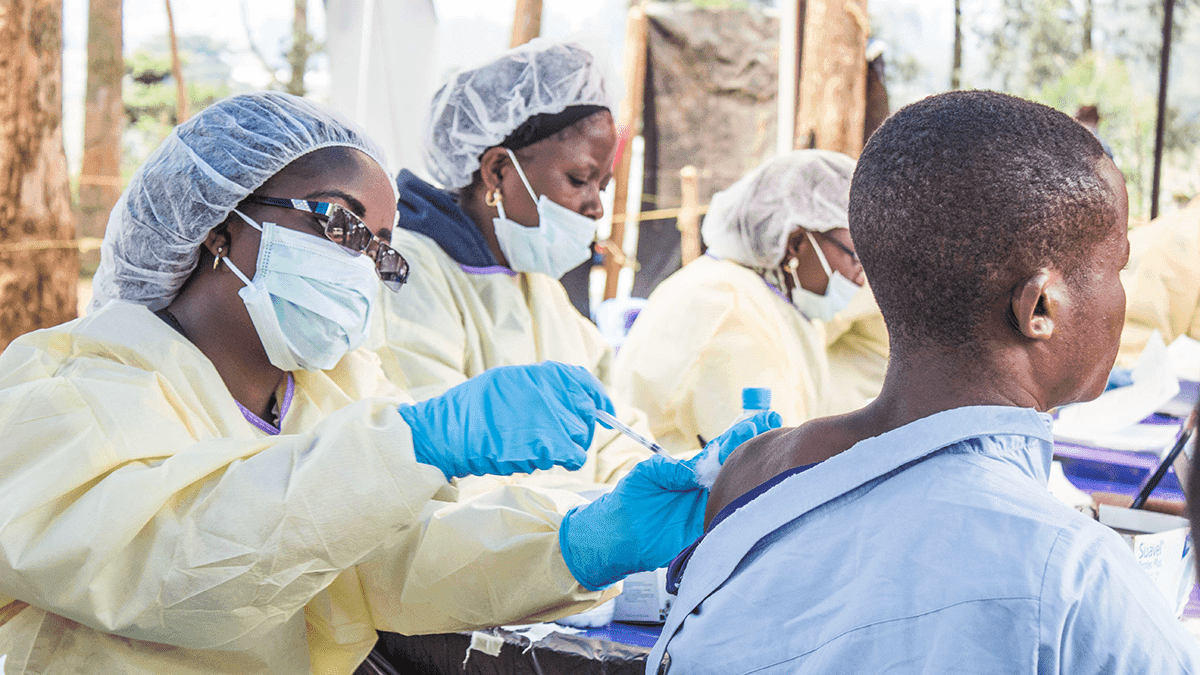

Take Ebola. Following the development of a vaccine candidate in 2005, a failure to prioritise epidemic preparedness and research meant that important safety trials, which can be done at any time, were not completed until the next major outbreak began nine years later. It meant that West Africa was faced with the world’s largest ever Ebola outbreak, unable to fight it with any vaccines or treatments.

Today, that is no longer the case. Thanks to the vital research conducted during recent Ebola outbreaks we now have a fully licensed vaccine and two effective treatments.

It’s crucial that we prioritise research as part of the global response to Covid-19. And alliances like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) are key to us developing the new vaccines we need.

However, at least $8 billion is still needed to address urgent research and development funding gaps. This includes $2 billion to develop Covid-19 vaccines and $1 billion to manufacture them, so that we can make the billions of doses required to reach everyone who needs one.

Vaccines must be available to all, regardless of where they have been developed

During the 2009 swine flu pandemic, poorer countries lost out on access to the vaccine as rich countries negotiated large orders in advance.

Today, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (Gavi) plays an essential role in making sure that the world’s poorest countries have access to life-saving vaccines. For example, a major partnership between Gavi and vaccine manufacturer Merck has helped to secure a vaccine stockpile for Ebola. It’s meant that 300,000 doses of the vaccine are available in case of an outbreak, and it is these doses that are being used in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

We can only begin to control the COVID-19 outbreak if vaccines, tests and treatments are accessible to everyone, regardless of where they have been developed or who has funded them. As long as the disease is out of control somewhere it is a threat to us all.

Everyone involved in vaccine development – from R&D funders to developers, manufacturers and governments – has an important role to play by working together and making sure equitable access happens in practice.

Routine immunisation should continue wherever safe and possible

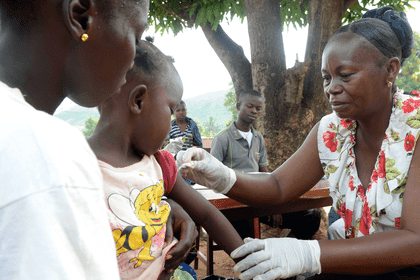

In the DRC, routine immunisation programmes have suffered due to the Ebola outbreak and ongoing conflict. Now, the country is also facing the world’s largest measles outbreak. Tragically, the number of people who have died from measles is already double that of those killed by Ebola, the vast majority of them children.

Globally, physical distancing policies in response to Covid-19 have meant that 14 major Gavi-supported vaccination campaigns – including polio, measles, cholera, HPV, yellow fever and meningitis – have all been postponed, as have four national vaccine introductions. Collectively these would have immunised more than 13.5 million people. And the Measles and Rubella Initiative has estimated that more than 117 million children across the world are at risk of missing out on receiving the life-saving measles vaccine.

As Covid-19 pushes health systems to the absolute limit, we must do everything possible to prevent countries from having to face multiple outbreaks, especially from diseases for which we already have safe, effective and low-cost vaccines available.

Major catch-up vaccination programmes will be an urgent requirement as soon as it is possible to implement them safely, and organisations such as Gavi will be crucial to ensuring that vaccines reach those who need them the most.

This World Immunisation Week is an important reminder that vaccines, as well as tests and treatments, are our only way to end the Covid-19 pandemic.